|

Drug courts offer second chances and better lives

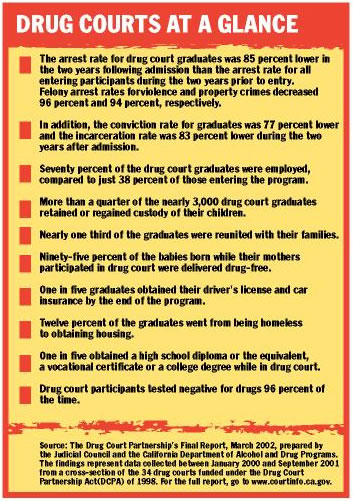

"It gave me my life back," says Olson, now a Ukiah gas station cashier by day, carpentry apprentice by night and volunteer mentor to troubled teenagers in his spare time. And recent data suggests that 40-year-old Olson's turnaround is not the exception. California's drug courts can reduce drug use, criminal offenses, homelessness and unemployment - and save millions in prison, jail and other costs, according to the findings of a study conducted by the Judicial Council and the state's Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs. "Drug and alcohol abuse play a major role in the majority of criminalcases that come before our courts," said Chief Justice Ronald M. George. "This study shows that drug courts are helping the justice system and the public by decreasing drug use, improving lives and protecting communities." What the recent study found, for example, was that the arrest rate for drug court graduates was 85 percent lower in the two years following admission than the arrest rate for all entering participants during the two years prior to entry. The number of participants with jobs nearly doubled to 70 percent at graduation. Twelve percent went from being homeless to having a home. And one in five advanced their education level while in drug court. And during the study's reporting period - January 2000 to September 2001 - it cost just $14 million in state Drug Court Partnership Act funding (along with some supporting funds) to save roughly $43 million in prison and jail costs alone, the study concluded. The report's findings came as no surprise to those involved in the drug court system. "It's certainly consistent with what we've seen nationally, particularly in pioneering states like California, Florida and Ohio," said Karen Freeman-Wilson, chief executive officer of the National Association of Drug Court Professionals. "It's our position," she said, "that this ought to encourage the state decision-makers to invest even more resources in drug courts, given the favorable results that they've seen thus far." Founded in Florida in 1989, the first structured drug court marked a groundbreaking alternative to traditional courts. Since then, some 700 such courts have sprung up nationwide, with 500 more in the planning stages. California saw its first drug court launched in Oakland in 1993; now there are more than 146 in 50 counties. Recently, California's drug courts have faced new challenges triggered by Proposition 36 (a voter-approved initiative generally requiring treatment instead of incarceration for those convicted of nonviolent drug use offenses) and uncertain funding. Drug Court Partnership Act The recent study is the result of the Drug Court Partnership Act (DCPA) of 1998, which provided court funding and called for an evaluation of the courts' effectiveness. Tracking a cross-section of the 34 DCP-participating drug court programs, evaluators found that most admittees had been using drugs for at least five years, were unemployed and had significant arrest records. Drug courts succeed in changing lives, judges and administrators say, for various reasons. The drug court team members - which include a judge, probation officer, treatment provider and others - all work together to help the "client" overcome his or her addiction and build a new life. Drug courts may vary by county in their requirements. They range from pre-plea to post-conviction programs lasting a year or longer, for example. And some focus solely on the mentally ill or teenagers or those involved in family law cases. But they all find common ground in their non-adversarial approach, ongoing judicial supervision, and a system of graduated rewards and sanctions. In addition, brief jail stints, commonly referred to as "flash incarceration," are generally considered crucial at times to re-focus faltering participants. Many describe the drug court judge as a caring parent of sorts. "It's basically tough love," says Superior Court Judge Wendy Lindley, who oversees Orange County's drug courts. The message is "we actually do care about you in the criminal justice system, but we require you to be accountable and responsible," she said. "For many, they have never received this kind of treatment."

Accountability required In Orange County's drug courts, where the drug-related recidivism rate for graduates hovers at just 11 percent, participants are required to earn their general education diploma or take English as a second language and get a job with a potential future. They can be subjected to home searches. And to graduate, they must pass a class in self-esteem and goal-setting at a nearby junior college. The fact that the class is on a real college campus itself delivers a powerful message to drug court participants, Lindley says. "What it says to them is: Hey, you can do anything you set your mind to," she said. "Most of them are living in their cars when we get them." Dianne Marshall, the therapeutic courts administrator for Mendocino County, explains that drug court goes far beyond monitoring someone's progress in a drug treatment program. It has as much to do with helping the participant rebuild a life, she says, and providing closely supervised time to practice living it. "We help people remove obstacles," she said. "We help them get their licenses back, and we help them get employment, go to school, get letters of reference, get on top of past-due fees and fines. . . . We try to eliminate the negative bricks in their backpack, the excess luggage that being a drug addict brings with it." Real human savings In the DCPA study, 20 percent of the drug court graduates got their drivers licenses and car insurance, 31 percent were reunited with their families, 28 percent retained or regained custody of their children and 8 percent became current in their child-support payments. The results of the study demonstrate "real human savings" as well as tremendous cost savings, says Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Stephen Manley, president of the California Association of Drug Court Professionals and co-chair of the committee that helped plan the DCPA study. Manley, who helped found Santa Clara County's drug courts, primarily sees the drug court judge as a "motivator" to those beaten down by substance abuse. "To me, the greatest challenge is to try and convince people who have given up on themselves to start believing in themselves once again and to start believing they can do things," he said. "You've got to try and convince them to take a chance on themselves." It takes humility on the judge's part, he says. And the judge needs to understand that relapse is part of the disease. "You look for progress," he said. "You never look for perfection."

After a seven-month residential drug treatment program, he was accepted into Mendocino County's drug court. Living at a homeless shelter and riding his bicycle in the rain to daily testing and counseling sessions, weekly court status hearings and a night job at a gas station left Olson completely overwhelmed. "I didn't see how I was going to do it," he recalls. At one point, he got caught driving with a revoked license and had to write 10 essays and spend 10 weekends in jail under the judge's orders. Olson's essays, which he had to read from the witness stand, are now part of a booklet circulated by the drug court staff. "Everyone was really watching what was going to happen to me," he said. "Basically drug court wasn't designed for someone like me. It was designed to stop someone from becoming like me." For Olson, drug-free for two and a half years now, it was the strict accountability, constant support and "hands-on" experience that helped him turn his life around. "I needed to learn how to live again outside of prison and jail," said Olson, who now regularly spends time with his 5-year-old daughter. And one day, he said, he realized that his senses were no longer flat. "The sky was blue and the grass was green again," he said. "I got it back. I can feel again. I go to the movies and I can cry and laugh and everything matters again."

Related Articles |

||||||||

|

||||||||