Bar pass rates under scrutinyUnaccredited law schools targeted in Sacramento By Nancy McCarthy

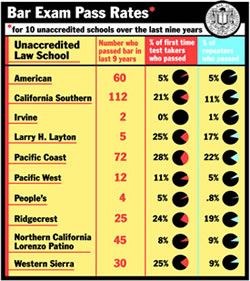

In the last 18 California bar exams, administered over nine years, just two graduates of the unaccredited Irvine University College of Law have passed the exam, neither on the first try. During the same time period, four from the People’s College of Law in Los Angeles and 12 from Pacific West College of Law in Orange passed the bar exam. Only nine graduates of the Southern California Institute of Law in Santa Barbara, accredited by the State Bar, passed during that time frame; 34 took the test at least once and more took it more than once. Most years, SCIL’s pass rate for its Santa Barbara grads is zero. Bar exam pass rates have declined steadily in recent years, both nationally and in California. According to the National Conference of Bar Examiners, 64 percent of would-be lawyers who took bar exams nationwide in 2004, the last year for which national statistics are available, passed. Some 28,110 people failed that year. In 2000, 65 percent passed and in 1995, the pass rate was 70 percent. Besides raising law student anxiety, the decline has stirred debate about the bar exam and the quality of a law school education and has attracted interest in Sacramento. In California, 48.2 percent passed the July general bar exam in 2004, 55.3 percent passed in 2000 and 59.4 percent in 1995. Gayle Murphy, the State Bar’s senior executive for admissions, says law schools’ “eventual pass rate” is a better yardstick to measure a student’s chances of passing the bar exam. She pointed to a 2003 study that broke down eventual pass rates, over three attempts: 90 percent of graduates of ABA-approved law schools eventually pass, compared to 68 percent who attend California accredited schools and 58 percent for graduates of unaccredited schools. “There’s a law school for everyone here in California,” Murphy said. Indeed, in addition to ABA-approved schools, California accredits 20 schools that meet rigorous requirements, and another 11 unaccredited schools and nine correspondence schools are registered with the bar and overseen by the Department of Consumer Affairs. Graduates of all those school may sit for the bar exam in California, one of the few states that permit students from non-ABA approved schools to take its exam. And they can take it an unlimited number of times. Murphy said the bar exam pass rate is not the sole criteria for choosing a school; students should look at the quality of the program, the faculty and administration and a school’s finances to make sure it is on solid ground. Historically, California has had “a very open process for taking the bar exam with minimal requirements and no limit on the number of times you can take it,” said Dean Dennis, chair of the Committee of Bar Examiners. “That’s the way California has opened itself up to many people to become a lawyer. The counter position is it’s a very difficult test so you have to really prepare if you are going to pass it.” But Sen. Joe Dunn, D-Garden Grove, is taking a hard look at the bar exam pass rates and the quality of the legal education provided by unaccredited and correspondence law schools and recently introduced a bill to transfer oversight of those schools from the state Bureau of Consumer Affairs to the Committee of Bar Examiners. “I have been concerned for some time about whether in fact completely unaccredited law schools, including correspondence schools, contribute to some of the problems we see in the bar, like lawyers pushing the ethical edge on issues,” Dunn said. He said a higher percentage of complaints about attorney misconduct involves graduates of unaccredited schools. In addition, “When you talk to judges, they will tell you the quality of lawyering is substantially less than that from accredited schools.” At a hearing Dunn held last fall, representatives of unaccredited and correspondence schools testified they provide a good education, disclose their bar pass rates and offer a low-cost opportunity to people who otherwise would have little chance of earning a law degree. But Dunn questions why California is the only state that permits prospective lawyers who graduate from unaccredited schools to sit for the bar exam. “Is California missing something or are the other 49 states missing something?” he asked. (Bar officials said a handful of states permit students to take their bar exams if they’ve been admitted in another U.S. or foreign jurisdiction.) Dunn said it is premature to suggest shutting down unaccredited schools, but he hopes to unify the regulation of all California law schools not approved by the ABA. Neither the State Bar nor the Committee of Bar Examiners has taken a position on the bill. George Gliaudys, dean of the Irvine University College of Law took issue with what he said is “an assumption that registered schools are providing a below-par education to its students.” In fact, he said, his school provides “the same course of study that everybody else does” and its students, mostly mid-career adults, must take the First-Year Law Students’ Exam (baby bar) to continue beyond the first year of school. Leonard Padilla, chairman of the University of Northern California Lorenzo Patino School of Law in Sacramento, denounced the Dunn bill as “an attempt to put us out of business.” He said Lorenzo Patino, founded in 1982, serves many students who have no interest in becoming a lawyer but want a law degree to advance in their careers. Padilla, a bail bondsman and bounty hunter, said he attended California-accredited Lincoln Law School “to learn the difference between robbery and burglary.” He took and failed the bar exam once, he said, “but I had no intention of ever practicing law.” Padilla called Lorenzo Patino a law school of last resort at the Dunn hearing last year, and said it accepts students who have been shown the door by other law schools, who he accused of ripping off law students by advertising their bar exam pass rates, accepting their tuition for two years and then expelling them. Gliaudys, Padilla and other executives of schools not approved by the ABA say their institutions fill a niche and serve a population that can increase the diversity of the California bar. Many of their students live in a geographically isolated area or one without a nearby ABA-approved school. They often have a fulltime job and a family. Generally, the program is at night, takes four years and costs far less than an ABA school. The schools sometimes have more relaxed entrance standards, taking into consideration work experience as much as, or more than, college grades. Some take students without a college degree. And some provide most of the lawyers in their local community. San Joaquin College of Law, for example, offers three-, four- and five-year programs at its Clovis campus, where 210 students are enrolled. Founded in 1939, the school is accredited by the State Bar and enjoys regional accreditation from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, a step above bar accreditation. It has produced about 1,000 graduates, says Dean Jan Pearson, including the elected district attorneys of most of the surrounding counties, about 60 deputy district attorneys, 21 judges and administrative law judges and the chair of the California Water Resources Control Board. Pearson said 28 percent of the lawyers practicing in the Fresno area got their law degree at San Joaquin, including 48 percent of the women lawyers in the Fresno area and 35 percent of the minority lawyers. The school’s cumulative pass rate is 85.4 percent, she said. “To me what’s really exciting is San Joaquin started out making opportunities and it really did that and changed the face of the legal profession in Fresno.” Another school accredited by the Committee of Bar Examiners is the Southern California Institute of Law. Dean Stanislaus Pulle, who received his law degree at England’s Kings College and attended Yale Law School, said SCIL’s graduates register an eventual pass rate of 45 or 46 percent. However, statistics kept by the bar show a zero pass rate for all but five of the last 18 bar exams for the Santa Barbara graduates. The rates for the Ventura grads were modestly higher. Pulle, who said he never took a bar exam, called the zeroes “very misleading” and attributed the low pass rates to a student population that is working fulltime, had lower grades in college and are paying for their legal education without student loans. He also said the “format and content of the bar exam is different from the way law school is taught . . . I’m not saying it’s unfair, I’m saying the bar pass rate is no yardstick to gauge the quality of education. I wish someone would really dispel that myth.” SCIL-Ventura grad Paul Hunt, who passed the bar exam on his sixth attempt, attributed his five failures to his writing style. “When I threw away all my bar stuff and did the same quality of test with a different writing style, lo and behold I passed,” Hunt said. He called the bar exam “rather flawed” with a “slanted” grading system. Hunt, 38, owns a mortgage business and hasn’t decided whether to practice law. But he said the Southern California Institute of Law was an excellent choice for him because it offered “a solid legal education” with a faculty that wants students to succeed and offers plenty of help. But Dunn is skeptical. “What you’re doing is filling the legal ranks in California with lawyers, at least in theory, that don’t rise to the level of quality you see in the other 49 states,” he said. “Lawyers hold an awesome responsibility on behalf of their clients. Lawyer education should not be ‘what the heck, why shouldn’t there be a school for you.’” |

||||||||

|

||||||||