Growing, and graying, attorney

|

||||||||

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

Los Angeles County Bar Association President Charles Michaels would prefer that law firms make accommodations for the older former partners who want and are able to continue to contribute.

He tells the story of a friend — a well-respected attorney who brought $600 an hour to the firm and scores of clients — who hoped to end his career at his firm but felt he’d earned some leisure time. Told he would have to continue billing 2,000 hours a year if he wanted to stay, he opted to leave.

At some firms, partners reaching 65 or thereabouts are not even given that choice. They’re often unceremoniously booted out, sometimes getting the bad news from people they considered close friends.

“There are too many lawyers too heavily focused on billables and making the American Lawyer’s top list for $1 million — that sort of thing,” says Michaels. “I’ve seen the demands that are placed on associates and senior lawyers to continue a billable requirement that I think is unhealthy for the profession and the individual lawyer.”

Thirty years ago, 1,500 hours seemed to be the billing norm for lawyers at corporate firms. Now, says Michaels, it’s 2,000, and it’s not uncommon to see senior lawyers bill 2,200 hours — or else. There are reasons for the increases, he says: global competitiveness as well as consolidation and mergers and fierce competition among law firms. Still, he adds, “It seems a shame that at the peak of careers in many firms, lawyers are either being forced out or required to maintain a level of billable hours that is not good for that lawyer.”

M. Laurence Popofsky, 71, well-known senior antitrust lawyer at Heller Ehrman in San Francisco, believes retirements should be handled on a case-by-case basis. But he sees real value in older managing attorneys stepping aside to allow a younger generation to take the reins, especially in what he calls a legal “world of free agency.”

“Direction by patriarch in the old-fashioned way has long struck me as anachronistic and ineffective,” Popofsky says. “I can only say that when I was the senior partner in a position as co-chair, I was convinced that for the firm to progress, stay together, confront the internationalization and globalization problems and inevitably stand, one had to have younger leadership. I think their understanding, their vision, their interrelationship with peers is a sounder basis on which to proceed than direction from on high.”

Nurturing of managers in their 40s and 50s, he says, contributes to “a culture of firm clients rather than individual clients. A firm is a lot healthier and more dynamic when everyone thinks of client X as a firm client rather than Larry’s client.”

Alan Rothenberg, a Los Angeles litigator and former State Bar president who has led the U.S. Soccer Federation and who has always had civic activities outside the office, is another attorney who believes the old guard “shouldn’t hog the business.”

He fully supports the idea of bringing younger people into management and so he left Latham & Watkins — which he says has a mandatory retirement age for partners at 65 and optional at 60 — of his own volition when he reached age 60.

The age deadlines forced him to think about retirement early, he says. “In my case, it worked out wonderfully,” even though he says he doesn’t hunt, fish, garden or paint. “What I really like is action — business action and community action.” So, since he retired, he founded a bank, where he serves as chairman, became chairman of a sports marketing firm and sits on several boards. He’s also president of the Los Angeles Airport Commission.

If Popofsky’s and Rothenberg’s belief in the graceful retreat of elderly management catches on, huge numbers of a generation that shows every indication of defying age stereotypes may have to adopt a new mindset.

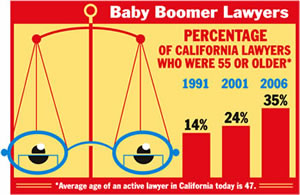

The average age of the active California lawyer today is 47. In 1991, 14 percent of active State Bar of California members were 55 years of age or older. In 2001, that percentage jumped to 24 percent, and last year it reached 35 percent.

Last year, the oldest of the nation’s 78 million Baby Boomers, those born between 1946 and 1964, turned 60. And, according to a number of surveys, many Baby Boomers, who generally are healthier and better educated than earlier generations, don’t plan to retire at age 65.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 29 percent of people in their late 60s are still working compared to 18 percent in the mid-1980s.

Signs that the over-60 crowd won’t go quietly into a proscribed life of golf and rocking chairs are illustrated by a U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) lawsuit against Chicago-based Sidley Austin Brown & Wood.

The age discrimination suit was filed on behalf of 32 unnamed former partners — including four in California — who were involuntarily downgraded or forced to retire. John Hendrickson, EEOC regional attorney in Chicago, says discovery on the case, which was filed in 2005 in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois and grew out of a 2000 EEOC administrative investigation, will be concluded this summer.

“There’s never been any real dispute that people who work for law firms — secretaries, file clerks and associates — are employees and would be covered (by anti-discrimination laws),” says Hendrickson. “In this case, we’re saying the Age Discrimination in Employment Act applies to partners of the firm who are not members of the executive committee or the management committee.”

Hendrickson encourages law firms to follow the business model. “If you want to get rid of somebody, you do it based on performance...That’s how General Motors lets people go. That’s how Ford Motor Company lets people go. That’s how Goldman Sachs lets people go.”

A decision in favor of the EEOC will demonstrate, Hendrickson adds, “that no employer is above the law, whether you’re among the most powerful law firms in the country or the most humble machine shop.”

There are the angry, ousted 32 Sidley Austin lawyers, all but about five of whom signed written letters asking the EEOC to represent them. And then there are attorneys like Theodore Kolb, 86, of counsel at McQuaid, Bedford and Van Zandt in San Francisco. “I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I retired,” says Kolb, who specializes in probate and trust. “I’m having fun...I enjoy the work. I enjoy the contact with people.”

Kolb, who began practicing law when “billable hours” was an unknown term, works about five chargeable hours a day now. He has clients who include the third generation of families who count on him to review the technical work and legal documents to make sure they cover everything the client wants.

He believes moving into an “of counsel” position in the later years makes good sense. For the attorney, such a system preserves the relationship with the firm and clients get the benefit of experience. “There are some lawyers who should have retired at 50 and some who hit the top at 65,” says Kolb, who is chair of the ABA’s Senior Division. “You’ve got to take it case by case.”

Hindi Greenberg, president of Nevada City-based Lawyers in Transition, says she does see more and more lawyers who are being asked to leave their firms.

“Thirty years ago, that never happened,” says Greenberg, who practiced in San Francisco. “They let them hang on whether they were contributing or not.” But, she adds, there’s a difference between dead weight and someone who’s not producing as much as in the past.

A large part of the trend to push out older partners is the desire by younger lawyers to make “astronomical sums.”

Being forced out takes a heavy toll, she says, noting that some ousted lawyers end up crying to her on the phone. “Career is a large part of a person’s identity,” Greenberg says. “ Even if you hate the job you’re at, being asked to leave still punctures one’s ego...People want to make their own choice.”

| Contact Us | Site Map | Notices | Privacy Policy |

| © 2025 The State Bar of California | |||