Bridging the worlds of neuroscience and the lawBy Diane Curtis

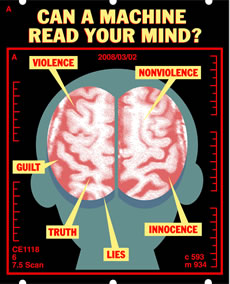

An Iowa scientist claims his “brain fingerprinting” has caught a serial killer and exonerated a man falsely convicted of murder. A San Diego CEO says his “No Lie MRI” can prove defendants’ innocence. A Massachusetts company boasts of offering “breakthrough deception detection.” All very tantalizing, respond some scientists and legal scholars. But also a bit premature. “I think we should be skeptical about these claims,” says Hank Greely, law professor at Stanford University and a leader in the new Law and Neuroscience Project headquartered at the University of California at Santa Barbara. “We need to not rush into it. But we also need not to ignore it.” It’s difficult to ignore. New studies are regularly emerging that confirm and further explain the use of brain scans to read a person’s mind.

Simply put, the fMRI displays and analyzes blood flow and changing oxygen levels to specific regions of the brain. A sudden demand for blood suggests activity in a particular area of the brain. The computer displays the most active areas with the brightest colors. “The new realization is that every thought is associated with a pattern of brain activity,” John-Dylan Haynes of the Max Planck Institute told Newsweek magazine. “And you can train a computer to recognize the pattern associated with a particular thought.” Well aware of the potential, limitations and ethical questions surrounding fMRI and other brain science discoveries, the MacArthur Foundation put up $10 million last year to create the Law and Neuroscience Project. The foundation describes the project as “the first systematic effort to bring together the worlds of law and science on questions of how courts should deal with recent breakthroughs in neuroscience as they relate to matters of assessing guilt, innocence, punishment, bias, truth-telling and other issues.” Former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor is honorary chair of the project, which is being led by Michael Gazzaniga of the SAGE Center for the Study of the Mind at UC-Santa Barbara with participation by more than two dozen universities. The project is initially being made up of three working groups of scholars and legal experts addressing addiction, brain abnormalities and normal decision-making as they relate to concepts in the law. Each group will review current research, identify gaps in knowledge and understanding and develop proposals integrating neuroscience into the legal system.

Greely, chair of the steering committee for the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics and co-director of the project’s Network on Differing Brains, sees real value in answers that neuroscience might provide that are relevant to the law. Further investigations into the workings of the brain might better help define the scope of an insanity defense, make better predictions related to sentencing or tell whether someone really is suffering pain or is biased, says Greely. He also notes that treatment alternatives may be found through neuroscience. “We may be able to figure out better ways to deal with criminals than warehousing. We may come up with better ways to deal with drug addiction.” But the biggest potential, he says, may relate to mind reading through such methods as the fMRI. “If that worked — and I think it’s a big if — I think that would transform a lot of law even if it weren’t admitted in trial but just used as an investigative tool.” Then he adds: “I want to stress that neuroscience is at the early stages. You can go wrong by thinking it’s more powerful than it is . . . It may transform the legal profession or it may not. I see our project as playing this kind of centrist balancing role.” Joel Huizenga, CEO of No Lie MRI in San Diego, thinks Greely and others are being too cautious. Huizenga says numerous studies have shown the fMRI can separate truth from fiction more than 95 percent of the time. “The front lights up when you’re lying and the back part when you’re telling the truth,” Huizenga says. “They’re wildly different.” Right now customers come to him to verify they’re telling the truth about sex, power and money, he says. He only tests individuals who want to be tested (the machine can’t get a true answer if someone moves inside the scanner, anyway) and would like the U.S. justice system to move towards that of Switzerland, which he says allows lie detectors to help prove innocence but not to prosecute. Greely says fMRI has been admitted in a few cases in U.S. courts but never for lie detection. An Iowa court ruled in 2001 that brain fingerprinting, a technique patented by former Harvard psychologist Lawrence Farwell, could be used in court in the case of a man who said he did not commit a murder for which he had been convicted. But the court made clear that because the brain fingerprinting, which reportedly reads brain wave responses, “is not necessary to a resolution of the appeal, we give it no further consideration.” Farwell has claimed that his machine helped prove the man’s innocence. Michael Begovich, deputy public defender in San Diego County and vice chair of the State Bar’s Criminal Law Section, is very interested in the possibility of brain scanning information being used in the courtroom if it proves to be a technique that can eke out the truth. However, he notes, it’s up to the courts to give the procedure a thumbs up. “You’re not going to spend the money for the test if the judge doesn’t allow you to put it into evidence,” says Begovich.

Judy Illes, who directed Stanford’s Program of Neuroethics and now heads the National Core for Neuroethics at the University of British Columbia, says she does believe that brain images will help in “providing further evidence that completes a story.” But, she adds, “it is not the story . . . A brain scan is just a brain scan. Our behavior is very complex because we are very complex people. We have moods, intentions, motivations, dynamics with other people. A brain scan is one piece of data to put into an equation that may have an impact.” Illes, who is working with Greely and others on the Law and Neurosci-ence Project, says it’s up to the scientific community to ensure that brain scans and other neuroscientific discoveries are used in an appropriate manner. And that means making sure that two questions are answered: Is it ready for prime time? Even when it’s ready for prime time, what does it really tell us? Others have raised an assortment of ethical questions surrounding new technologies to read minds: If the brain can pinpoint tendencies toward violence, what can or should be done about it? And does such a tendency reduce a person’s responsibility for that violence? Does everyone have a right to freedom of thought? Is it OK to add brain scans at airports to try to pinpoint terrorists? Could you use a brain scan to detect bias in witnesses and jurors? |

||||||||

|

||||||||