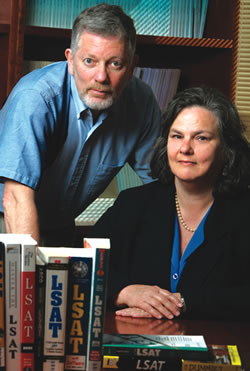

Researchers suggest expanding criteria for law school admissionBy Diane Curtis

A successful trial of tests that measure such attributes as empathy, research abilities, stress management and writing capabilities has made “a compelling case” for moving ahead on efforts to expand law school admissions criteria beyond the LSAT, according to a pair of UC-Berkeley researchers. In the final leg of a six-year, three-phase study, retired law professor Marjorie Shultz and psychology professor Sheldon Zedeck found that tests measuring 26 “effectiveness factors” foreshadow future performance in the legal profession much as the LSAT (Law School Admissions Test) is said to predict success or failure during the first year of law school. Unlike the LSAT, the performance factors do not have the racial differences seen in the LSAT, Shultz and Zedeck say. “Definitions of ‘merit’ and ‘qualification’ have become too narrow and static,” the Berkeley professors wrote in their report, “Identification, Development, and Validation of Predictors for Successful Lawyering.” “They hamper legal education’s goal of producing diverse, talented and balanced generations of law graduates who will serve the many mandates and constituencies of the legal profession.” The academics are not recommending doing away with the LSAT or consideration of grades, but with adding other tests that focus on likelihood of professional effectiveness. “To base admission to law school so heavily on LSAT scores is to choose academic skills (and only a subset of those) as the prime determinant of who gets into law and law-related careers that demand many competencies in addition to test-taking, reading and reasoning skills,” they wrote. The work of Shultz and Zedeck stemmed from a goal of then-Dean Herma Hill Kay a decade ago to find ways to enlarge the pool of applicants to law schools in a post-affirmative action era. “To admit primarily on the basis of LSAT test scores and grades to a professional field that has great importance to our society seemed short-sighted,” Shultz and Zedeck wrote. “We believe the exploratory data reported here make a compelling case for undertaking large-scale, more definitive research on the pre-admission prediction of lawyer performance.” Richard Sander, a UCLA professor whose research has concluded that affirmative action at elite schools hurts minority chances of making it through law school to become successful lawyers, said in an interview he has no problems with the Shultz-Zedeck approach: “If you can develop a test that does a better job of what makes a good lawyer, that seems like a really worthwhile goal,” Sander said. But he added that such a study cannot come up with substantive results if only one or two schools are surveyed. In addition, he said, there’s no guarantee that another test will be race-neutral. Shultz said she is not surprised that Sander has no objection to the study continuing. She corresponded with about a dozen lawyers who initially bridled at the idea of the study, suggesting that its goal was to make “an end run around affirmative action.” But after long correspondence, “to a person, they ended up saying, ‘I’ve come to believe you are honestly working on a justifiably broader notion of merit,’” Shultz said. They abandoned the perception that she and Zedeck were trying to lower the quality of students accepted to law school. “Our test is clearly race-blind and merit-based,” she said. “We didn’t design the method to produce minorities. It’s an existing method that has been used in the employment sector.” The first phase of the study resulted in a list of 26 factors in eight categories considered important for successful legal practice. The categories are:

The researchers interviewed hundreds of lawyers, law faculty, law students, judges and clients and asked them what qualities they look for in a good lawyer. The 26 factors that emerged from the interviews range from analysis and reasoning, interviewing, fact-finding and questioning, to writing, speaking, listening, negotiation skills and passion and engagement. The researchers also came up with 715 examples illustrating poor to excellent performance on each of the 26 factors as well as rating scales by which to assess a lawyer’s effectiveness. Phase II involved choosing off-the-shelf and writing original tests to measure the performance factors. And in Phase III, they collected data to assess whether performance on the tests by 1,148 volunteer lawyers correlated with actual lawyer effectiveness. Because traditional indicators like the LSAT and grade point averages do not predict performance as a lawyer, “other predictors focusing on prediction of post-graduate performance should be explored,” the researchers concluded. The job now, says Shultz, is to find funding for a more detailed analysis of performance predictors and the tests that measure them. She and Zedeck have met with the Law School Admissions Council (LSAC) on the possibility of such funding, which she estimates could be from $3 million to $5 million. “If further research confirmed the validity of performance-predictive tests, then the new measures would open up an array of valuable options in admissions practices,” the report said. Shultz noted that officials at LSAC, among many others, have lamented the amount of emphasis, especially in magazine ratings, that has been placed on the LSAT. The end of affirmative action in California, through Proposition 209, afforded a motive for finally spending time and money on more accurate predictors of success in the legal profession. “It provided an occasion to rethink what we define as merit,” Shultz said. |

||||||||

|

||||||||