ic garden that supplied the vegetables. A cowboy who

does needlepoint. A voracious reader, opera-lover and church-goer who bungee-jumped over

Africa’s Victoria Falls, the tallest bungee jump in the world.

“Palmer

is very hard to label,” says Jim Garrett, a partner with Morrison and Foerster and a

longtime friend. “God broke the mold when he made Palmer.” “Palmer

is very hard to label,” says Jim Garrett, a partner with Morrison and Foerster and a

longtime friend. “God broke the mold when he made Palmer.”

Garrett nevertheless offered up a laundry list of descriptives: free

spirit, independent thinker, judicial, sharp, straightforward, reserved, good heart and

good values, great sense of humor and the ability to laugh at himself. “He wants to

do the right things,” Garrett concluded.

Contra Costa County Superior Court Judge Maria Rivera, another

longtime friend, thinks Madden “will be an ideal bar president. He is a visionary,

but is also extremely pragmatic, and he has a particular skill at conducting very

efficient, very effective meetings. I think the bar will be delighted with that.”

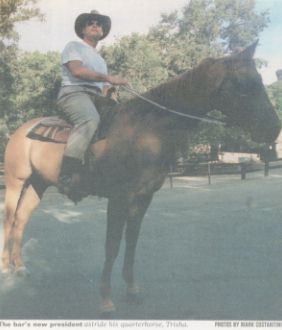

On a recent summer morning, Madden started the day as he often does,

riding his quarterhorse Trisha through the hills surrounding his Alamo home, built on 20

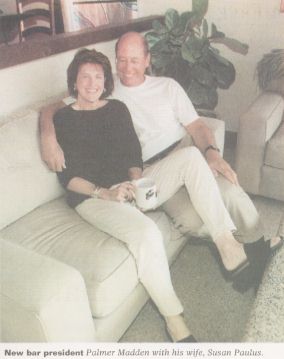

acres he bought in 1972. He and his wife, attorney Susan Paulus, share the property with

two more horses, two dogs and four chickens who live in a henhouse. The couple left

high-pressure jobs last year, after 25 years in practice.

Now an arbitrator and mediator, Madden opened Palmer Brown Madden ADR

Services in January 1999, ending 13 years in the Walnut Creek office of McCutchen, Doyle,

Brown & Enersen, including a stint as managing partner. Although he still considers

himself a practicing lawyer, Madden’s more relaxed life allows time for travel and

the pursuit of a seemingly endless list of interests. That pursuit might be deferred in

the coming year since Madden’s time likely will be consumed by the bar presidency, a

job which frequently requires a fulltime commitment.

“I see this as a great opportunity to be of service,”

Madden says. “I have the time, and I’m interested in the things the State Bar is

working on.

“Part of the reason I ran was because all my life, when there

were challenges, I rose to the challenge. This was another challenge.”

Born Sept. 19, 1945, in Milwaukee, Madden was the third child of Helen Brown

and Milton Eppley. A German Jew whose parents emigrated from Heidelberg to escape

pre-World War I anti-semitism, Eppley (who had changed his name from Epstein) was a

financier who owned Midland Finance, a regional investment firm. The couple named their

only son Milton Louis Eppley Jr. Born Sept. 19, 1945, in Milwaukee, Madden was the third child of Helen Brown

and Milton Eppley. A German Jew whose parents emigrated from Heidelberg to escape

pre-World War I anti-semitism, Eppley (who had changed his name from Epstein) was a

financier who owned Midland Finance, a regional investment firm. The couple named their

only son Milton Louis Eppley Jr.

When Madden was three, his 42-year-old father died of a stroke. His

mother remarried three years later, and Madden and his sisters were adopted by their

stepfather, Lou Madden, who also changed their names.

Madden started a somewhat checkered boarding school career at age

nine. Asked where he enrolled, he answered with a wry smile, “there isn’t a town

I didn’t go to boarding school in. I was not the easiest student to have in

class.” His academic career improved considerably in high school at

Connecticut’s Kent School, and he was accepted at Stanford University, where he

majored in history, studied in Italy for nine months and spent a year in India.

After graduating, Madden worked on the political campaign of a

college friend’s dad, James Collins, who was elected to Congress from Dallas. Madden

followed Collins to Washing-ton, serving as an administrative assistant, a job that piqued

an interest in becoming a politician. Two years as a community organizer for Vista put

that idea to rest.

He decided instead to go to law school and enrolled at Boalt Hall at

UC Berkeley. “I was very interested in my classes and did well to my surprise,”

Madden said — well enough that he was selected for the law review. “Law school

woke me up,” he said.

Madden’s roots as an attorney grow deep: he is the

great-great grandson of William H. “Billy” Herndon, law partner of Abraham

Lincoln in Springfield, Ill., and his mother’s father was an attorney in Wagner,

Okla. Madden’s roots as an attorney grow deep: he is the

great-great grandson of William H. “Billy” Herndon, law partner of Abraham

Lincoln in Springfield, Ill., and his mother’s father was an attorney in Wagner,

Okla.

Madden joined Morrison and Foerster in 1973, becoming the only

attorney in the San Francisco firm who wore his hair in a ponytail. Jim Garrett, the first

partner with whom Madden worked, said the hairdo caused “a fair amount of comment by

older partners, and people used to kid him about it.” No one asked him to get rid of

the ponytail, however.

In 1981, he joined Van Voorhis & Skaggs, a five-attorney firm in

Walnut Creek which grew to 25 lawyers before merging with McCutchen in 1985. In his

practice, Madden specialized in commercial litigation, including partnership disputes,

contract and fraud claims, real property disputes, construction litigation, intellectual

property matters and environmental cases.

Madden stayed with McCutchen until last year, and his election makes

him the fifth McCutchen partner to serve as State Bar president.

During his years of active practice, Madden developed an interest in

pro bono work and alternative dispute resolution and he began to volunteer with the State

Bar. At one point, he negotiated an arrangement under which he worked half-time for

half-pay, freeing him to write and to take on pro bono work. He taught at law school and

became the lead editor and writer at CEB on the law of politics, covering such issues as

conflicts of interest and campaign contributions. He joined the board of the Kennedy King

Foundation, raising money from the Contra Costa County business community to help send

low-income students to college.

Among his biggest achievements, Madden counts his work on the Mono

Lake litigation, which went to the Supreme Court and forged new environmental law, and a

1995 $15 million jury verdict, the largest in Contra Costa County until last year.

When a backlog of civil cases grew in the county, Madden joined a

panel of attorneys created to ease the situation, meeting once a week with a judge to

mediate four or five cases. “I became interested in the process that way,” he

says, “and my own cases were settling that way.”

All the while Madden’s practice was flourishing, he pursued an eclectic

variety of outside interests. Before finishing law school, Madden began what would become

an 18-month project — design and construction of a 3,000-square foot house on his

Alamo acreage. He and his former wife knew nothing about building, Madden said, and

enlisted the help of an architectural student and friend who gave them the benefit of his

expertise at the rate of $4 an hour. He still lives in the house, whose massive sliding

glass doors disappear into a wall to open the living room to the outdoors. Madden admits,

though, that the windows have always leaked. All the while Madden’s practice was flourishing, he pursued an eclectic

variety of outside interests. Before finishing law school, Madden began what would become

an 18-month project — design and construction of a 3,000-square foot house on his

Alamo acreage. He and his former wife knew nothing about building, Madden said, and

enlisted the help of an architectural student and friend who gave them the benefit of his

expertise at the rate of $4 an hour. He still lives in the house, whose massive sliding

glass doors disappear into a wall to open the living room to the outdoors. Madden admits,

though, that the windows have always leaked.

In 1978, Madden, his wife and two partners opened the Creative

Learning Center, a pre-school whose philosophy was to find a child’s strengths and

encourage them. The school was sold in 1986, but continues to operate.

He also opened a restaurant in 1981, designed, he said, “to

combine do-gooding with commercial enterprise” by offering natural foods in a

business that was a model of energy efficiency. An organic garden at the site was the draw

for customers, who then dined at the restaurant; the money was reinvested in the garden.

Madden’s wife ran the place and he worked as the greeter in the evenings after work.

The restaurant, since sold, is still in business.

Despite his many interests, Madden said he does not consider himself

a joiner. He and Paulus are active in their church — she as a grief counselor —

and they travel extensively. He skis, sails, scuba dives and swims a mile three times a week. A voracious

reader, he reads “anything and everything,” usually two or three books

simultaneously, and leans toward science, history (with a particular interest in George

Washington), religion and junk novels.

Paulus, who was head of litigation for McKes-son Corp. in San

Fran-cisco and met Madden when they were on opposite sides in a large civil case,

describes her husband as “the most creative person I know. He’s terrific on his

feet, a wonderful speaker, he’s funny, he’s caring.” What sets him apart,

she adds, is “his unwillingness to do something just because it’s

accepted.”

Those qualities, as well as his business savvy and mediation

experience, should serve him well at the helm of the State Bar, where he says a key goal

will be to remove the board of governors from day-to-day operations and focus instead on

broader policy questions. He hopes the board will create a priority list that includes

issues such as multidisciplinary and multijurisdictional practices, diversity in the legal

profession, unauthorized practice of law, the future of MCLE and a look at the attorney

discipline system.

Madden does not come

from a long history of bar activism and does not consider himself a bar

“junkie,” but he is a fan of lawyers and a strong supporter of the organization

which he says benefits California attorneys. Without the bar’s discipline and

admissions operations, he points out, anyone could practice. “The core parts of the

bar are in good shape and need to be protected,” he says. “We need to put

politics behind us and focus on what the bar does well.” Madden does not come

from a long history of bar activism and does not consider himself a bar

“junkie,” but he is a fan of lawyers and a strong supporter of the organization

which he says benefits California attorneys. Without the bar’s discipline and

admissions operations, he points out, anyone could practice. “The core parts of the

bar are in good shape and need to be protected,” he says. “We need to put

politics behind us and focus on what the bar does well.”

Paulus thinks Madden is just the man for the job. “The board of

governors is at a point where it needs some creative thinking combined with

consensus-building and persuasiveness,” she says. “Palmer has all those

qualities better than anybody I know.” |