| President Lincoln in his first inaugural address urged a nation restless

to fight to abandon the war-mongering, bellicose threats and calls for separation so

popular in 1861. Imploring the nation to unite around common ideals, public service,

justice, truth and virtue, Lincoln appealed to what he phrased "the better angels of

our nature." In these simple words, Lincoln captured a great truth about human nature

and instructed us, by example, to frame our most important appeals to one another based on

this truth. From the beginning of the American republic, lawyers and the judicial system

were to have a central role in maintaining democracy. The Founders' confidence in lawyers

and judges to protect the public interest related not only to their special competencies,

but their role was regarded as vital to a self-governing society.

In fact, the

role of lawyers was recognized as so important to the republican form of government that

even the regulation of lawyers was left generally to the lawyers themselves. Accordingly,

until fairly recent times (1927 in California, 1938 in Virginia), the profession had few

institutionalized systems for regulation. Today, though every state has some system for

regulating lawyers, nearly all of these are controlled almost entirely by lawyers. In fact, the

role of lawyers was recognized as so important to the republican form of government that

even the regulation of lawyers was left generally to the lawyers themselves. Accordingly,

until fairly recent times (1927 in California, 1938 in Virginia), the profession had few

institutionalized systems for regulation. Today, though every state has some system for

regulating lawyers, nearly all of these are controlled almost entirely by lawyers.

This privilege of self-governance is the quid pro quo for the public service expected

from this learned profession. In every state, the bar has created enforceable standards of

conduct for lawyers. Violations of these standards may result in a variety of sanctions,

including license revocation.

Yet without something more at work, lawyers will not rise to the level of

professionalism needed in today's society. To elevate professionalism and the profession,

lawyers must volunteer to meet higher standards. And they must do so with such commitment

that anyone aspiring to be a good attorney knows what those standards are, and what is

required to meet them.

Herein is the heart of professionalism. Not that conduct complies with rules, but that

conduct is ethical because lawyers are persons of integrity.

The American Bar Association said in its 1998 statement Promoting Professionalism,

"The ethical integrity of the lawyer must be our profession's hallmark and call for

public confidence. Ethics is not just a set of rules. It is a value system, a mind-set, a

responsibility that must remain constant in the lawyer's consciousness."

Moreover, in addition to acting ethically, the lawyer must strive to be perceived as

doing so. A reputation for integrity should be a cherished asset of every lawyer.

To this high calling, I add these standards of true professionalism: civility and, as

able, peacemaking.

The legal profession, by its very nature, is confrontational, adversarial and

combative. Though more evident in trial work, even business transactions involve assertion

and protection of opposing interests.

To avoid exacerbating the conflict and tension inherent in the tasks of the profession,

an attorney should be civil in manner, communication and conduct. Civility, when practiced

well, can ease confrontation and create an environment in which more peaceable solutions

will sometimes emerge. Though clients may pressure the lawyer to act otherwise, an

attorney whose civility effects more temperate responses may actually lead to better

outcomes for all parties.

One of the greatest law teachers in American history was Karl Llew-ellyn. "You

must represent your client to the best of your ability," he noted, "and yet

never lose sight of the fact that you are an officer of the court with a special

responsibility for the integrity of the legal system."

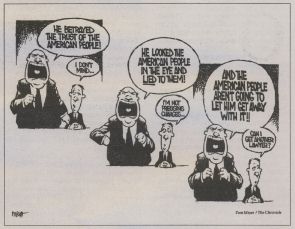

The duty of advocacy is so influential that those of us who fall for the "good old

days" of expecting lawyers to pursue truth and justice, to act as officers of the

court, to have no duty to win a client's case by virtue of mistake, unethical conduct,

publicity or other such considerations are in the minority. The prevailing view is that

lawyers must do anything short of theft to advance the client's cause.

Note that I say short of theft. I think it is too generous even to say "anything

short of theft or dishonest conduct." In some of the highly visible cases getting

particular public attention, there appears to be a pattern of disingenuous, if not

outright dishonest, conduct on the part of lawyers.

The duty of advocacy is now so well established that lawyers believe they are compelled

by self-protection to do everything possible to advance the client's interest. After all,

each client is a potential plaintiff. If a client expects a lawyer to use "all means

necessary," a lawyer must question his commitment to higher standards on the grounds

that he may be sued if he follows it.

Even

courts, particularly in criminal cases, have fueled this fear by requiring lawyers to file

appeals and make arguments that have only the slightest connection to due process

concerns. A lawyer is put in the position of making silly, frivolous motions and arguments

because court rulings have led lawyers to believe they can be criticized, even sued, if

they fail to assert every conceivable argument. Even

courts, particularly in criminal cases, have fueled this fear by requiring lawyers to file

appeals and make arguments that have only the slightest connection to due process

concerns. A lawyer is put in the position of making silly, frivolous motions and arguments

because court rulings have led lawyers to believe they can be criticized, even sued, if

they fail to assert every conceivable argument.

Highly visible cases have brought a new dimension to the profession. Lawyers become

"talking head" celebrities, needing to look after their own book deals,

opportunities to appear on television and movie rights. No longer is ambulance chasing

disdained as performed only by the lawyers at the margin of the profession:

"high-class" ambulance chasing has become a way of life for many lawyers.

In many high-profile cases, the justice system is used for non-legal means. Filing a

suit for political harassment, leaking pleadings to the press for embarrassment, trying to

stop a merger for economic extortion and other uses of the legal system for patently

non-legal objects has further prostituted the profession, giving us the appearance of

being gun-slingers for hire, not independent professionals giving counsel and aid to

clients.

When greedy lawyers lived at the margin of the profession and even of a society that

did not respect them, one could take comfort in the fact that their conduct was not

normative. At least "good lawyers" did not act that way.

Sadly, such conduct is increasingly becoming normative. Large firms, reputable firms

and firms discounting their history of professionalism and ethics let the temptations of

big clients and big cases entice them to new lows.

Nevertheless, despite my disappointment in the erosion of professionalism among

lawyers, I am satisfied that the better angels will prevail. Society's disdain for

outrageous conduct by lawyers will result in a reaction. Already, lawyers and bar groups

are responding to this disdain by aggressively pursuing ways to improve the level of

professionalism and, in turn, the public image of the profession. Lawyers themselves feel

the disgust and disillusionment and are anxious for ways to turn things around.

Finally, there are the better angels themselves, persistent and abiding. They will

prevail because of individuals who will choose to be guided by them.

Trial lawyer Phillip C. Stone became president

of Bridgewater (Va.) College in 1994 and is immediate past president of the Virginia Bar

Association. This column is adapted from a speech he gave recently at the University of

Virginia Medical School. He earned his law degree from the U.Va. School of Law in 1970. Trial lawyer Phillip C. Stone became president

of Bridgewater (Va.) College in 1994 and is immediate past president of the Virginia Bar

Association. This column is adapted from a speech he gave recently at the University of

Virginia Medical School. He earned his law degree from the U.Va. School of Law in 1970.

|