|

appears to be filibustering, reading from the

trial transcript for much of the afternoon. And this is a bench trial,

so there is no audience, no jury to impress with sweeping gestures and

colorful language. Frankly, it's a little boring - even the judge

makes a wry comment or two. appears to be filibustering, reading from the

trial transcript for much of the afternoon. And this is a bench trial,

so there is no audience, no jury to impress with sweeping gestures and

colorful language. Frankly, it's a little boring - even the judge

makes a wry comment or two.

Although she's slouching at the attorneys'

long table, and if one is vigilant, she can be caught - once or

twice - rolling her eyes at the defense's monotone monologue,

Nobumoto's own argument is all business. Animated and concise, she

summarizes testimony given by alleged victims. Then she breaks for

lunch in the criminal court's cafeteria.

"It's nothing like a jury trial; in the end,

passion doesn't win the day with the judge," she said.

Later in the week, Hylland was found guilty of 27

charges and sentenced to a 13-year prison term. But because practicing

law without ever having had a license is a misdemeanor, most of the

prison time comes from convictions of felony grand theft.

It bothers Nobumoto that shysters so often prey

on recent immigrants and the poor - she is committed to diversity

and plans to make minority and disability issues the hallmark of her

presidency.

And

it frustrates her that UPL is difficult to prosecute under current

state laws.

"We as a bar need to lobby Sacramento, make

this a felony. We need to look at prosecution, not just prevention,"

she said.

Had there been a jury in this court, Nobumoto

would have talked at length about the real harm of UPL: the house lost

by one woman forced to declare bankruptcy after dealing with Hylland;

the visitation rights that were damaged by Hylland's failure to

appear. This is the harm that cannot be assuaged by a few thousand

dollars in restitution.

"Much of this harm is not economic; it's the

havoc done to these people's families," Nobumoto said.

In less than a half-hour, three defense attorneys

have approached the cafeteria table, appearing in succession as if

swept in Nobumoto's direction. "You know what makes her a great

prosecutor?" said Andy Stein, a criminal defender who took a seat

opposite the prosecutor and stayed to chat awhile. "She's more

interested in doing the right thing than winning." In less than a half-hour, three defense attorneys

have approached the cafeteria table, appearing in succession as if

swept in Nobumoto's direction. "You know what makes her a great

prosecutor?" said Andy Stein, a criminal defender who took a seat

opposite the prosecutor and stayed to chat awhile. "She's more

interested in doing the right thing than winning."

That's not to say she tends to lose her cases:

Of 20 felony trials she prosecuted for the county's central trials

division, 18 resulted in guilty verdicts, two in plea bargains.

Stein, a private practitioner from Bellflower,

has opposed Nobumoto in a handful of felony trials, and, he estimates,

as many as 50 court appearances.

"I like having someone like her on the other

side. She's not easy. She's not soft. She's hard-nosed and

tough, but fair," Stein said. "If you're not prepared, you're

going to get hammered by her. She'll take your head off in the

courtroom."

Little gets in the way of Nobumoto, 49, when it

comes to doing what she believes is the right thing. Not even the

sight of blood.

She recalled an incident early in her career in

which she badly sliced her finger on a defective chair, in the middle

of a preliminary hearing. Bleeding profusely and in terrible pain, she

wrapped her finger in napkins and continued arguing as if nothing had

happened.

"Finally, the judge leans over and says, 'Ms.

Nobumoto, do we have a problem?' I said, 'Yes sir, your honor.'

I remember I was too afraid to stop because of (the defendant's)

right to a continuous preliminary hearing."

During her term as the State Bar's first woman

minority president, Nobumoto will be working in the D.A.'s employee

relations division, where she can take on fewer cases and steer clear

of long days in court. But she's already thinking about where

she'll land when her year is up. During her term as the State Bar's first woman

minority president, Nobumoto will be working in the D.A.'s employee

relations division, where she can take on fewer cases and steer clear

of long days in court. But she's already thinking about where

she'll land when her year is up.

Right now, she's thinking arson.

"The science aspect is appealing to me; the

evidence these investigators find tells the whole story - it's

really amazing," Nobumoto said. "(And) they're such horrific

crimes - not only were these people killed, but they suffered to

death."

Then again, she muses, she also is interested in

fraud, in helping to knock people like Hylland, the unlicensed

practitioner, out of commission.

Whatever she sets her sights on, her record

virtually seals her success. In addition to an alphabet soup of

professional affiliations, Nobumoto's 12-year career has included a

promotion to the county's elite career criminals unit and

recognition as 1998 Prosecutor of the Year by the Century City Bar

Association.

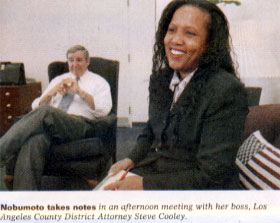

"She's one of our best; we're proud of all

her accomplishments and we're happy to have her here in any

capacity," District Attorney Steve Cooley said. "But believe it or

not," he added, "we do have a few other able attorneys who can

fill in for her" during her presidency.

Nobumoto's downtown office is pretty much

wall-to-wall boxes as she prepares to move into the new position,

which happens to include a slightly plusher office in another

building.

"Just that seems like withdrawal. I should be

happy, right?" Nobumoto said. "(But) I'd rather be in total

squalor, doing the real stuff." "Just that seems like withdrawal. I should be

happy, right?" Nobumoto said. "(But) I'd rather be in total

squalor, doing the real stuff."

Stein said that early on, other attorneys could

tell Nobumoto would be a great prosecutor by the compassion she showed

for victims and in some cases, for defendants with sympathetic

circumstances. She didn't showboat, he said, and she didn't always

throw the book at defendants - especially those accused of crimes

related to poverty - as some zealous young lawyers might.

"She's a good lawyer, but she's a better

human being and that's what it's all about," Stein said.

"Everyone knew right away Karen was going to be a good D.A. because

she's real, she has real-life experience."

Born in Cleveland and raised in Los Angeles,

Nobumoto received her J.D. in 1989 from Southwestern University School

of Law. Her mother was a schoolteacher; her father, a social worker.

"Government service is in our blood; I was

raised in a community-service environment," Nobumoto said.

Nobumoto's family is also filled with artists:

her 38-year-old sister, Lisa, is a jazz musician; the family also is

related to noted jazz musician Charles Lloyd. A Dallas cousin is a

painter, and Nobumoto's home is dotted with the woman's

African-American themed oils and pastels.

Active in the bar since she was admitted at the

end of 1989, Nobumoto was elected to the board of governors just in

time to help rebuild the bar following its dismantling in 1998. In

winning the presidency, she beat out all four members of the

third-year class.

She is being sworn in this month at the State

Bar's Annual Meeting in Anaheim, but for the last six months she has

traveled extensively in preparation for her post.

It's difficult to believe law is the

tough-talking attorney's third career, following stints as a

marketing representative for IBM, and - even harder to imagine - a

preschool teacher.

But at her hilltop home near Pasadena, Nobumoto

produces a scrapbook filled with sponge paintings, crayon scrawls and

rudimentary lettering. She still remembers all her former students,

though the kids are now teen-agers: Who was better with fingerpaint;

who had trouble forming the letter "c"; who was a troublemaker;

who was particularly precocious.

"I had 3-year-olds. When I walked in the door

in the morning, I was surrounded by hugs," Nobumoto said. "You

walk in and get nothing but love - pretty cool job."

When you walk into Nobumoto's contemporary,

two-bedroom house, you get Kiki, a skink with a prehensile tail. Kiki,

12, has a large cage to herself in the light-filled foyer, where the

reptile lazily greets guests. She's alone because she refused the

company of her male counterpart, Blue, named for the color of his

tongue. Blue was granted asylum in the kitchen.

The reptiles have been with Nobumoto throughout

her legal career, replacing an iguana who died. Both skinks together

are much smaller, and according to Nobumoto, are each easily twice as

intelligent as their predecessor.

Bar junkies still talk about the time Nobumoto

appeared at a bar commission meeting in the early 1990s with Kiki

peeking from her long, dark mane.

"(But) I've reformed," she insisted.

"That's a lesson for the ambitious young lawyer - whatever you

do at the bar, they'll still be talking about it 12 years down the

line."

Kiki and Blue are firmly entrenched among the

black-laquered, Asian-influenced furnishings in Nobumoto's home, but

they share the space with the rest of her small zoo: Banana Boat the

box turtle lives in the bedroom; Rasta the chinchilla occupies the

television room; Yin and Yang, a pair of green parakeets, separate the

living and dining rooms; and Dom Perignon, the cocker spaniel, pretty

much has the run of the place. Kiki and Blue are firmly entrenched among the

black-laquered, Asian-influenced furnishings in Nobumoto's home, but

they share the space with the rest of her small zoo: Banana Boat the

box turtle lives in the bedroom; Rasta the chinchilla occupies the

television room; Yin and Yang, a pair of green parakeets, separate the

living and dining rooms; and Dom Perignon, the cocker spaniel, pretty

much has the run of the place.

As she travels the courthouse halls, Nobumoto

seems to collect people - they just gravitate her way as she speeds

from one floor to another, from Cooley's expansive office to the

spartan cafeteria to the courtroom. It's impossible to slow her

momentum, but she manages at least a chirpy greeting - even if

it's only a partial sentence - "Hey, how're . . . great!"

- tossed in the direction of colleagues, friends and admirers.

At home, she collects things. There are the pets

representing land, sea and air, of course, as well as 300-plus bottles

of wine in the cellar, more than 1,000 VHS tapes and dolls from around

the world.

The dolls represent different points of travel,

serving to remind Nobumoto that there was a time she took pleasure

trips, not just the business variety.

A major movie buff, her shelves contain examples

of nearly every genre from the 1970s to the present, especially

comedies: In the "A" section, it's "Action Jackson" to

"Austin Powers." Her all-time favorite movie, though, is "Gone

with the Wind."

Although

Nobumoto enjoys sharing her many wines and champagnes with guests, she

cannot bring herself to crack open any of her 1990 bottles of Cristal

or Dom Perignon.

"I didn't even crack one when I was announced

bar president," she said. "I don't know what occasion's going

to be special enough." |